We picture the urban context as a multiform being. We see it as an aggregate of elements that differ from each other in terms of who’s using them (pedestrians, cars, etc.), the activities carried out in them (settled, transient) and the time spent in them, as well as the degree of conservation and architectural protection they present.

These elements have one thing in common. City parks, pedestrian and vehicular zones, squares and car parks, as well as the so-called “non-places” such as train and bus stations and airports, are all spaces where individuals live in the community and fulfil their social needs. It is because of this shared characteristic that we can gather them under one big umbrella that we’ll call urban context.

Chaotic? Undoubtedly. But also surprisingly fascinating if we look at the sociological implications. Preserving what already exists, recovering as-yet undeveloped spaces, ensuring the right connections between the various areas, giving a sense of homogeneity: all this contributes to creating the reality that surrounds us.

And imposing some order on it.

Rio 2, 2800K, 19W/m Go to the project and credits

The urban planner who designs cycle paths, redevelops city parks and connects all these spaces to the nodal points of urban transport has a structured idea of sustainable development for the future. It is by building these spaces that he leads the city’s inhabitants to put his initial strategic idea into practice in their daily lives. Indeed, the future reality of that same community will be based on a set of elements of the urban context studied in advance, “on the drawing board”.

Therefore, we could say that a city’s identity is built and expressed through the use of its public places by its inhabitants, and that these spaces quite faithfully reflect the nature of its society.

One time, I arrived in Ljubljana towards evening; my hotel was located near a large city park.

I asked at reception what the quickest way was into the city centre by foot, and they said, “Turn right here, go across the park, you’ll find yourself …”

“I’m sorry, did you say across the park? At night?”

“Yes, go across the park and you’ll come out in a small square, from there …”

I left the hotel at around 10 pm and looked over at the park more out of curiosity than with any intention of going in. I spotted a girl jogging, and then another – in fact there were quite a lot of people exercising in the park at that late hour.

It seemed like another world to me, and maybe it was, because, as you may have already guessed, the park was well lit.

The tale of a female traveller on holiday in Slovenia

From social needs to social media needs

We said earlier that the individual’s relational needs are satisfied in the community within the framework of the urban landscape, and that the social spaces that allow these needs to be fulfilled can be defined as the urban context.

The town square, in the sense of an architectural place dear to the heart of the Italy of Comuni (municipalities), had an extraordinary social value, concentrating the needs of political, business, civil and religious aggregation in a single space. Even the surrounding architectural elements such as porticoes, created as a consequence of the buildings’ living space being extended, were consecrated as spaces for public use because of the great social utility they furnished. They allowed people to walk undisturbed, sheltered from the rain and excessive heat, they provided a moment of rest for the elderly and weary, and shelter for the homeless, and they gave shops room to display their artisanal products, facilitating their business transactions.

Today, our social needs include our activity on social media: as individuals, we enter public discourse through the pixels of the photos of ourselves we take and share.

How successful tourism is in a city also depends on the quality and quantity of the social posts about it. The Instagrammability of its sights and secrets, in other words whether these are able to inspire people to post a myriad of photos of them on social media, can directly influence the ability of a city to become attractive to tourists and, consequently, to fill its public coffers.

Urban Light, Chris Burden, LACMA (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

As long ago as 2017, a survey1 by the British insurance company Schofields Insurance found that a full 40% of respondents from the millennial generation said they chose a holiday destination based on its Instagrammability. According to an article in the Verge2, restaurant and bar owners ensure public success with interior design based on the looks that are a hit on Instagram. Care is taken to make the decor as photogenic as possible: that way, visitors will be inspired to take photos and selfies that, once online and with the appropriate name checks, will make a place famous and popular as the posts go viral.

If we view Instagram and Pinterest as the ideal virtual archives in which to find new travel ideas and inspirations, then it is a short step to extend that view from a restaurant’s decor to a city sight. Architectural elements, views and artistic installations that make up the urban fabric can be curated to serve as the perfect backdrops to shots designed to attract likes, acting as a social driver for tourism.

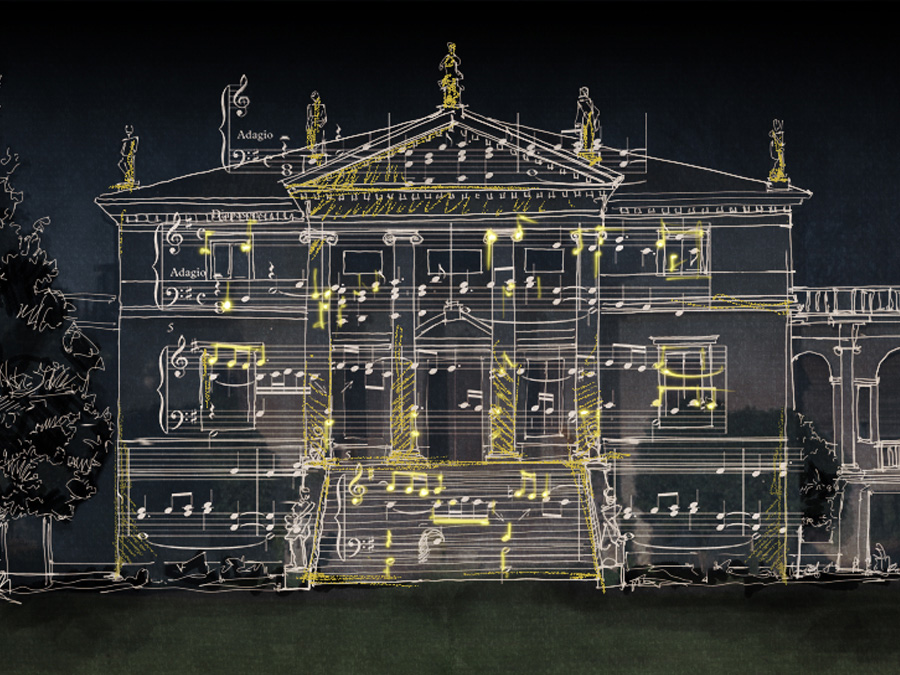

From our point of view, we can’t help but reflect on the role that the right lighting can play in making a city Instagrammable from dusk to deep into the night. We need only think of how much tourists are attracted by coloured light projected on building facades or by RGBW projectors in fountains.

1, 2: see bibliography below

#urbanselfie, Instagram

Quite unintentionally, we found out for ourselves how selfies and the Instagrammability of a place are now a reality to be reckoned with during our shoot in Istanbul at the Çamlıca Mosque. Our light profiles seemed to set the rules for where to stand when tourists took their selfies: here yes, there no.

O tempora, o mores – as our distant ancestors would say. Lighting designers may as well take this into account when rethinking light in an urban space.

Rio 2, 19W/m, version with customized installation and 2200K colour temperature Go to the project and credits

Neva 7.2, RGBW, 75W, 26°x58° Go to the project and credits

The 24-hour city

Let’s take a closer look: with the right light we can achieve three main objectives:

🔶Improving perceived safety. Remember our friend in Ljubljana? Light makes people feel more at ease when crossing an open space or collecting a bicycle parked at the station.

Rio 2, 3700K, 19W/m Go to the project and credits

River 2.2, 3000K, 20W Go to the project and credits

And, from there, it’s easy to identify the second objective.

🔶 Humanizing the urban context in which people live by making more use of public space and making the process of building a collective dimension a more tangible one.

🔶 Increasing the Instagrammability of a city, and thus its degree of attractiveness for tourism, by garnering publicity based on the spreadability of social content.

Alex Chinneck, Opificio 31, Milan Design Week 2019

The room to manoeuvre in the study of urban lighting can vary greatly depending on whether the context to be lit is an existing space, with architectural structures where the lighting needs to fit in seamlessly, or is part of an original project.

Depending on the case, we can decide whether our light will aim to enhance certain elements, to amaze, move and create an experience (to be shared on Instagram, of course!) or to facilitate an activity. The particular circumstances of a given project will then determine how broad (or narrow) the range of choices is for the lighting fixture.

Whatever the lighting objective, all options of course need to comply with:

⚖️ the standards for outdoor lighting (e.g. EN 13201 in Europe),

⚖️ local laws against light pollution,

⚖️ the instructions of organisations charged with protecting the architectural and landscape heritage.

But let’s take things slowly as we enter the urban jungle.

Follow the flâneur

Let’s open out a map of a modern metropolis on the table: we can imagine that we are wandering through the streets like modern-day flâneurs, people who appear to be simply loafing around but who are actually reflecting on the urban landscape around them and its many anthropological implications.

Having donned his hat and grabbed his walking stick, our flâneur will take a walk at sunset, ça va sans dire, trying to sum up what it means to illuminate an urban space.

Around 1850, the poet Charles Baudelaire began asserting that traditional art was inadequate for the new dynamic complications of modern life. Social and economic changes brought by industrialization demanded that the artist immerse himself in the metropolis and become, in Baudelaire’s phrase, “a botanist of the sidewalk”, an analytical connoisseur of the urban fabric.3

3: see bibliography below

With our map open on the table, we’ll trace a route through the city with our finger, starting in the pedestrian zones; in the next instalment, we’ll wander through the squares, the areas open to traffic, the stations and finally the city’s parks.

The reorganisation of cities through the creation of pedestrian zones has been going on for many years, and is inextricably linked to sustainability and the focus on tourism, as well as trade and hospitality. This trend is now sadly reinforced by the new health emergency, which is likely to lead cities to rely much more on walking and cycling than on potentially crowded public transport.

Colonising the unexplored

Sometimes a city’s administration decides to create a new urban space, causing the inhabitants to take possession of a place that simply did not exist before and to start living and carrying out activities there. These grey areas lie between existing sectors and become connecting areas, allowing previously unimagined possibilities to flourish.

This is the case in Paris, where a new district has been created in the area between the famous business district of La Défense and the adjacent municipality of Nanterre. These two centres have been joined by the construction of a 600 m pedestrian promenade. The new space offers cultural, entertainment and shopping possibilities with a sports arena, and commercial, educational and hospitality structures.

In a case such as this, the lighting design goes hand in hand with the architectural design, so there is plenty of room to manoeuvre – and, in this specific case, to install in the pavement recessed profiles with diffuse light.

Rio 2, 2800K, 19W/m, version with customizable length Go to the project and credits

The same drive-over fixtures were also chosen for the area in front of the marina in A Coruña.

We’ll put our cards on the table (next to the map): you’ll see a lot of these profiles as you make your way through this post.

The truth is, they’re something we’ve become famous for. We sometimes amuse ourselves by imagining how far they would stretch if we lined up end to end all the ones we have installed so far :)

Rio 1.2, 2800K, 12W Go to the project and credits

If the pedestrian zone is located right next to a river, lake or sea, and the lighting fixtures could be exposed to flooding, there’s the IP68 version, with the same ingress protection as used for underwater fixtures – it’s what was chosen for the promenade along the Vistula River in Warsaw.

This profile can withstand any environmental conditions because it is guaranteed to function both above and below water.

Fitting in seamlessly

As we follow our flâneur through the streets of the city, we see him linger in the busiest spots, observing tourists’ behaviour with an amused look.

If the urban space already exists, and the architectural elements that set it apart also exist, the lighting design will seek to fit in naturally.

The choice might fall on a compact, unobtrusive LED solution, as in the example below, to minimise impact and still provide effective lighting for pedestrians.

Bright 1.0, 4000K, 2W, diffuse optics Go to the project and credits

And what about the Instagrammability of this view at night? It’s a picture postcard in itself.

As we stroll along, we notice that the choice of wall-mounted step light is also unobtrusive.

On tourist walks where you don’t want to obscure the view of historically significant buildings, these devices do the job without drawing attention to themselves.

And that’s not all – these step lights tick all the boxes:

🔶 the light is directed downwards and only where it is needed, reducing the problem of light pollution;

🔶 if the fixtures are chosen with extremely wide optics, such as asymmetrical optics, long stretches can be lit with just a few lighting fixtures spaced far apart;

🔶 just a few lighting fixtures that use energy-saving, low-maintenance LED sources.

An easy win for the city treasurer!

Look up ...

Our flâneur takes a closer look at the lighting fixtures that are the archetypal part of street furniture: the projectors mounted on posts – on lampposts, in fact.

We have optics specifically designed for lighting pedestrian zones or footpaths, so the choice is between different types of light emission depending on the usage of the space we are lighting. Let’s look at them in detail:

Siri Blvd 2.0, A: pedestrian zone / B: footpath, distance between fixtures: 20 m, mounted on 4-m pole

🔶 The optics designed for the pedestrian zone (A) are symmetrical and illuminate the entire area around the lamppost,

🔶 Footpath optics (B), on the other hand, are extended longitudinally to avoid shadows and thus maintain a good level of illuminance.

... Look down

The trend among urban planners appears to be to make cities more pedestrian friendly, and lighting technology is following suit, putting individual wellbeing at the centre of innovative luminaire development.

The idea is that light can be modulated in a way that respects our biological rhythms, helping to reduce stress levels and maximise energy or feelings of relaxation.

Without launching into a full discussion on human-centric lighting here, which would lead us to talk more about interiors than urban landscapes, we can at least mention two variables that are important for producing lighting that is as comfortable as possible: quantity and tone. Warmer lights are better tolerated and influence our circadian rhythms less.

The use of filters to imitate natural light and shade effects on paths can make urban walking more relaxing because the resulting effect calls to mind a visual experience typical of a natural landscape, unconsciously triggering the feelings of relaxation typically experienced in that environment.

On the stroke of midnight ...

Continuing to walk through the city as the night grows darker, our flâneur reflects on the fact that from sunset to dawn the need for urban lighting is not constant. Continuous lighting in a place that does not require it is a waste of resources and an invasive presence in the natural environment.

We’ve talked about humans and their psychological wellbeing, but our view of the night sky and the health of the flora and fauna that inhabit our own spaces also need to be considered when thinking about city lighting.

Intelligent lighting systems are able to adapt to changes in the environment based on the information they collect about their setting. Installing a fixture with a built-in dimming device for the middle of the night (virtual midnight) means the light output can be gradually reduced when it is not needed, both saving energy and reducing light pollution.

Siri Blvd 2.0, 3000K, cycle path, distance between fixtures: 30 m

We have addressed the subject of urban lighting, examining the social aspects of lighting in public places, and focused on lighting pedestrian zones. Keep walking with us through our illuminated cities, and in the next article we will explore car parks, vehicular zones, roundabouts, parks and stations.

Bibliography

1 Independent, https://www.independent.co.uk/travel/instagrammability-holiday-factor-millenials-holiday-destination-choosing-travel-social-media-photos-a7648706.html, 10/10/2020

2 The Verge, https://www.theverge.com/2017/7/20/16000552/instagram-restaurant-interior-design-photo-friendly-media-noche, 10/10/2020

3 Wikipedia, Flaneur, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fl%C3%A2neur, 12/10/2020

Have you lit an eminently Instagrammable corner of your city with our lighting fixtures?